- Home

- Sara Shepard

The Elizas Page 9

The Elizas Read online

Page 9

“Just don’t send it to my family!” I say haltingly, almost in a shout. I swallow hard, embarrassed by my flurry of emotion.

“I didn’t mean family,” Laura says. “Unless they work for Entertainment Weekly or People. Do you know anyone from there? Do you know any BookTubers? Any Bookstagrammers?”

“I don’t even know what those words mean,” I admit.

“Oh. Okay. No matter! Oh, but also? I haven’t given out your phone number yet, but don’t be surprised if reporters figure it out and start calling you.”

“How are they going to figure it out?” I cry, feeling a clutch in my chest. “Do I have to talk to them?”

“Absolutely not. I don’t want you giving away anything about the book before it comes out. I think it should be a huge mystery—who is this Eliza person? Is her book true or false?”

“The book is false!” I almost scream.

“I know that. I’m just saying, people will wonder now. You officially have mystique. The marketing and publicity teams are over the moon. And then, once the book drops in stores, you’ll go on a tour.”

“A tour?” I repeat, ludicrously, as if I’ve never heard the term.

“Signings. Readings. Q and As.” She clucks her tongue. “Most debut authors don’t even get an offer to do a tour. This is a big deal. Be happy!”

I can already feel the panic coming on. “But what if people start asking me crazy questions during the events? Like, personal things? Things I don’t want to answer?”

Laura chuckles. “Then don’t answer them. It’s not like this is some sort of test where you have to fill in all the blanks. But you really should do a tour, Eliza. The book business is about building relationships. You can’t operate in a vacuum.”

“Thomas Pynchon does,” I babble. It’s the only thing I know about the author. I haven’t even read any of his books. I started V., but I read the same page about twenty times, thinking there was some sort of major printing-press mistake and all the sentences had been rearranged. The second page was just the same.

Laura has been saying something about Thomas Pynchon that I haven’t heard. I catch up with the conversation as she’s going “—at least drum up some social media presence, okay? Instagram. Facebook. Snapchat. I don’t care. Say something about Dorothy and Dot, your inspiration for the characters. I bet after your pool fiasco you have a lot of new friend requests. And look, I hate to drop this on you, but you know your editor, Posey? She’s in LA right now. She wants to have lunch with you at the Ruby Slipper Café—I think it’s in Beverly Hills. It’s probably to talk strategy about the pool thing and how you can drum up even more buzz for the book. Can you do today at 12:30? She’ll be expecting you.”

“I didn’t fall into that pool to drum up buzz for the book,” I say quietly. “I need you to understand that.”

“Of course you didn’t,” Laura assures me. “But I’ll take that as a yes about meeting Posey. Now, listen, please be on time, because Posey is very busy.” I hear her other line ringing. “Good luck, darling! She’s going to love you.”

Before I can respond, she bids me adieu and hangs up. And I stare at the phone and then at the gray morning sky out the window, trying to figure out what the hell just happened.

My gaze falls to the four large boxes on the floor. I’d received them on Saturday, the day I left for the Tranquility. Each bears my publisher’s logo on the side; just beneath that, in joyless font, it reads: The Dots, Eliza Fontaine. I sit up, lean forward, and pull one box toward me. It doesn’t take much of an effort to pry the cardboard flap open with my fingernails and wrench the top copy free.

The book feels heavy in my hands. The pages, deckle-edged, are pleasing to touch with the tips of my fingers, and the paper gives off a heavenly smell. The cover is slick and pink, like the inside of a mouth, with two dark-haired women, one taller, one smaller, standing side by side. Dot and Dorothy. My two main characters.

I think about something I can write about them on social media. Something innocuous. Most of what I’ve posted on Instagram are pictures of scary dolls and figurines I’ve seen at junk shops. But today, I hold a copy of my book up to my face, snap a picture, and post it on Instagram. T minus four weeks, I write as the caption. I don’t know what else to say.

But just as Laura has predicted, an account whose name is a jumble of letters and numbers gives me a like. So do three others. And then up pops a comment: Why’d you jump into that pool?

I swallow hard and look at my book again. I turn to my author photo on the back flap. It’s my face—pale, red-lipped, and saucy—and it’s my hair, wild and black—but it doesn’t really look like me. It looks like someone with confidence, panache. Someone who knows what the hell she’s doing. Someone who wouldn’t get shoved into a pool.

I don’t know what happened, I mentally compose as a response to the post. But hopefully, soon, I will.

• • •

On my way to the Ruby Slipper Café, which is on the most touristy stretch of Beverly Drive, I text Desmond Wells to ask if he got a response from the Palm Springs PD yet. It’s been enough time. Most people would get a call back already. But Desmond doesn’t reply. I feel snubbed. What’s that guy got to do right now that’s better than talking to me?

My phone rings again, startling me. I look at the screen. It’s Gabby.

“What’s up?” she says cheerfully when I say a cautious hello.

I stop in front of a soap store that has a chubby cherub as its logo. “Not much. You?”

“Oh, just working. Lots to catch up on from what I missed yesterday.”

I can hear Gabby’s keyboard clacking in the background. I bet she’s talking to me on a headset. “So I’m just making sure you’re . . . okay. Are you at home right now?”

“Gabby . . .” I clear my throat, realizing that perhaps this is an opportunity. “I really, really didn’t try to commit suicide that other night. You believe me, right?”

“Um . . .”

I hear her breathe in to say something—probably that she doesn’t—and I cut her off. I can’t bear another announcement of mistrust in my mental stability. “But also, how did you guys know I was in the hospital?”

“. . . What?” Gabby’s voice sounds far away.

“Well, when I woke up, you were there. All of you. How did that happen, exactly? Did a doctor call you? Someone from the hotel?”

Gabby coughs. More typing. “They found your driver’s license in your purse. And somehow that connected you to Mom. You should ask her—she’s the one who got the call. But then she called me, and we rode to Palm Springs together.”

“So you got there the morning I woke up? Or the night before?”

“That morning. When we got there, you were still sleeping. The doctor filled us in on what happened, officially.”

Officially. I roll my jaw. Her story seems believable. I’m not sure what I’m trying to catch her in, exactly. I just feel like there’s a big hole in my brain when it comes to that night. Something major I’m not remembering.

“Why did you take the blame for the vodka the first time we met?” I blurt out.

“. . . Huh?”

Across the street, a toddler throws herself down on the ground and starts to wail. Her mother crosses her arms over her chest and stares up at the cloudless sky.

“You should have said I got it out,” I say. “You should have made my mother smell my big glass of vodka. Why didn’t you? I’m sorry about that, by the way. I was a huge asshole.”

There’s a strange noise at the back of Gabby’s throat. “I don’t remember a big glass of vodka, Eliza. Are you sure it happened?”

“It happened. I wrote about it in the journal I kept at the time.”

“Well, you were always good at telling stories.”

Clearly this is some sort of ruse. Gabby has to remember. “And why did you never get angry when I took that cashmere sweater Bill got you for Christmas and wore it to that party and got beer all over it?

Why didn’t you ever tell me to stop putting weird shit in your bed? Why didn’t you say what really happened when I scared you in that coffin?”

“Where is this coming from? Why does this matter?”

The toddler has now stood up and is clinging to her mother’s leg. I watch as they hobble along together toward the crosswalk. “I just thought of it,” I say weakly. “I just want to know.”

“You sound strange,” Gabby says. “Should I call Mom?”

“Jesus. I’m fine.”

I hang up, fuming. I stare into the soap-store window. All the sales associates are wearing angel wings and body glitter and walk in mincing little steps. I will never go into that store, I decide. No matter how great the soap is.

How could Gabby not remember that vodka incident? It’s so significant. I can still picture every detail: the fury on my mother’s face, the thrill I felt at how easily I could manipulate Gabby, and the hitch in her voice, too, when she said, Maybe you shouldn’t be doing this. And then how, once Gabby took the blame for the vodka, it was all put away so quickly, as if it was best left unexplored.

Could I have made something like that up? But if I had, what was the real thing that happened instead? Had Gabby and I met and played Uno on the couch? Watched the Disney Channel? Traded Pokémon cards? That wasn’t me. That was never me. The only other option, then, is that she’s lying—she does remember, but she doesn’t want to talk about it. But why wouldn’t she want to talk about it? Especially considering I apologized.

It occurs to me I never found out why Gabby called. Not that I’m calling her back now.

Ruby Slipper Café, the restaurant where I am to meet Posey, is bare bones and unpretentious for Beverly Hills, a dark little place with crowded, wobbly tables and loud Brazilian music playing. As I step inside, every table is full. I look around. I’ve only met Posey on a blurry Skype screen, which means a large percentage of people in this place could potentially be her. I stand at the back of the line for food, every so often getting jostled by other customers.

Every time someone bumps me, my whole body ripples with discomfort. The buzz of voices, the smell of coffee, the low bass line of music . . . I feel too exposed. Unsafe. Too many people are staring. Just as I’m thinking this, a man at the far end of the room glances up at me and holds my gaze. He’s wearing tinted glasses and has a long, thin nose and a squared chin. A Yankees cap is squashed on top of his head, tamping down frizzy, graying hair. I stiffen. A long time ago, before I was afraid of airplanes, I was in New York City with my mother and a man in a raincoat snickered at us from a nook between buildings, opened his coat, and flashed his penis and wrinkled testicles. I’ve never forgotten his face.

That’s it. I can’t be here. I’m not ready to be out in the world—or maybe someone is watching me. Folding in my shoulders, I squeeze past two men ogling the pastries and step out to the front porch. Traffic whizzes past. Knots of pretty girls in high shoes sashay down the sidewalk. My lungs have hardened in my chest. My fingers shake as I fumble for my phone in my pocket—I need a ride home, now.

“Eliza?”

A tall woman with kind eyes stands at the little gate that separates the café from the street. She has at least a foot on me. Her arms and legs hang apishly low. Even her fingers are spindly. She’s got a candy floss fluff of black hair around her head, she’s wearing a strappy sundress despite the fact that it’s only 60 degrees and gloomy, and the sundress’s fabric pulls tightly against her swollen, pregnant stomach.

“Posey?” I say almost inaudibly.

“Yes!” She sandwiches my hand between hers. “Did you just get here? Shall we go in?”

The fingers on my other hand are still wrapped around my phone. “I, um—”

But she’s already pulling me into the restaurant. “It’s hideous of me that I’ve waited so long to come and see you. I mean, your book is practically out in the world! But I had to go through the IVF procedures for these”—she gestures to her belly—“and that seemed to take forever. Do you realize they have a vaginal wand in you every day? You can’t have a life. And then there was the morning sickness—I practically couldn’t leave the house.” She leans over herself and speaks to her stomach. “Why have you made it so hard on me? Couldn’t you have given me a break?” She uses a barking, militant voice.

“How many are in there?” I ask nervously as we walk up the stairs.

“Three.” Posey grins. “Three little boys.”

“Whoa.”

Posey grabs a menu and walks to the back of the restaurant like she’s a regular. She gestures for me to sit at a booth, and I don’t know what else to do but comply. I will talk to her for a few minutes, I reason. Then make an excuse and go. Surreptitiously, I peek at my phone and cancel my Uber request. I glance around the room. No one is staring at me anymore. Maybe I’m okay. I feel safer now that I’m not alone.

Soon enough, there are three sandwiches, a big bottle of juice, and an enormous slice of carrot cake I’d seen behind the glass in front of Posey. I order a smoothie with acai berries, but I can’t fathom drinking it. “Now,” she says, lacing her hands under her chin and peering at me. “Tell me everything. Tell me about you.”

I shrug and place my smoothie down without spilling it, which is a wonder, because my hands are still trembling quite badly. “Oh, well, you know. I’m nothing special.”

“The world is fascinated with you right now. You’re the mysterious author who flung herself into a pool.”

“I didn’t fling myself,” I say quickly, and then I cock my head. “The world?”

“Well, maybe not the world, but a lot of people. I have to admit we added a little fuel to the fire—we said the woman in the novel goes through quite an ordeal, and perhaps creating that character was too much for you. Perhaps you were exorcising your own demons, which led to the incident.”

“But . . .” I’m astonished. “That’s not true!”

“All the more reason for you to explain that in interviews after the book is published,” Posey chirps happily. And before I can protest that, she goes, “So. How did you come to write The Dots? Just so we have our stories straight.”

This is just Posey’s job, of course, and it’s natural she’s curious. She bought my novel, gave me an advance that equaled probably ten years of a typical twenty-something’s salary, and now she wants it to succeed. I can’t hold these questions against her, though the whole rise-to-infamy thing makes me feel . . . dirty. Like I’ve sold out—and I haven’t even sold anything yet. Successful books should be judged by literary merit and literary merit alone, shouldn’t they?

There’s another thing. None of my other drowning incidents were publicized—there was no reason to publicize them, as I wasn’t anyone of note. But if someone wanted to dig, they’d find some records about me. The guy and his son who’d lugged me out of the Pacific Ocean in Santa Monica might come forward with a report. Or the janitor who came in to clean the Days Inn hot tub and saw me lying facedown in the bubbles. I could just see that story in print: She wasn’t even staying with us, the janitor would say. Didn’t have a key card or anything. I don’t know how she got into the Jacuzzi area, either, as it’s usually locked tight. And she said there was someone after her, except I didn’t see anybody . . .

I feel Posey waiting for my answer. I don’t know what propels me to say what I say next, I don’t know what drives me to make the leap. It just comes out. “Halfway through my junior year at UCLA, I got a brain tumor.”

“Like Dot?” Posey asks, hand on the side of her face. “Good Lord!”

“Kind of like her. A similar tumor—I stole that detail because I knew how it worked and could guess what the treatment for it was.”

Posey narrows her eyes. She has somehow gotten a piece of lettuce on her cheek, but I don’t want to embarrass her by calling attention to it. “What do you mean you could guess the treatment?”

“My treatment was kind of a blur. They operated immediately, and then I was in

a sort of . . . haze.”

“Really?” Posey leans forward and scrutinizes my scalp. “You must have had a good plastic surgeon. I don’t see any scars.”

“LA, right?” I laugh, a little mirthlessly, a lot awkwardly. “They used a new technology where they didn’t have to do much cutting. Anyway, I guess I’m okay now. Amazingly. Everyone says it’s a miracle.”

Posey shuts her eyes. “And here I’ve been whining to everyone about IVF and carrying three watermelons. That must have been horrible for you. I’m so sorry.”

“It was, mostly because I’ve always been afraid I was going to get a brain tumor,” I admit, hating that I’m practically echoing my mother’s words. “It was a self-fulfilling prophecy. Anyway, after I recovered, I went back to my parents’ house. I was stuck in my room, feeling out of it, and I needed something to do, so this is what I wrote.”

Posey’s eyes gleam. “And you wrote this book in just days, didn’t you?”

“Well, not days, but it only took a few weeks. I couldn’t stop. I had to keep going until I was done.”

“You were in a fugue state.” Posey sounds delighted. “I’ve always wanted to meet someone who’s gone through it. What was it like? Did you take on a different personality?”

“Uh . . .” I wish I had. That sounds so interesting. “No. Not really. I just had this idea, suddenly, and I wanted to make sure I wrote it before I forgot it.”

Posey laces her fingers over her belly. “You authors and your processes. Do you know that I work with a man who wrote his entire novel on the subway to and from his shitty job at some doctor’s office on the Upper East Side? He did the whole thing on his BlackBerry. Poor thing didn’t even have a new phone. He had to use that awful keyboard.” She leans forward. “So why did you write this particular story? What led you down this path?”

“I just started writing. First it was to try and put words to my experience—you know, being sick. So I wrote about a girl who was stuck in a hospital room looking at the steak house across the street. She imagined herself there, with a cast of interesting characters. I gave her someone to talk to. And then it just . . . morphed.”

Heartless

Heartless Alis Pretty Little Lies

Alis Pretty Little Lies Flawless

Flawless The Elizas

The Elizas Stunning

Stunning Pretty Little Secrets

Pretty Little Secrets True Lies

True Lies The Good Girls

The Good Girls Burned

Burned Perfect

Perfect Pretty Little Liars

Pretty Little Liars Unbelievable

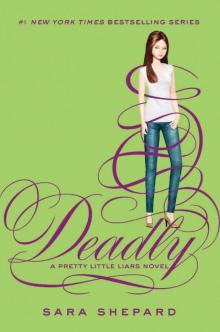

Unbelievable Deadly

Deadly Vicious

Vicious Crushed

Crushed The First Lie

The First Lie Cross My Heart, Hope To Die

Cross My Heart, Hope To Die The Lying Game

The Lying Game Wicked

Wicked Follow Me

Follow Me Seven Minutes in Heaven

Seven Minutes in Heaven The Perfectionists

The Perfectionists Killer

Killer Twisted

Twisted The Amateurs

The Amateurs Safe in My Arms

Safe in My Arms Wanted

Wanted Everything We Ever Wanted

Everything We Ever Wanted Two Truths and a Lie

Two Truths and a Lie The Visibles

The Visibles Ruthless

Ruthless Hide and Seek

Hide and Seek The Heiresses

The Heiresses Reputation

Reputation Never Have I Ever

Never Have I Ever Toxic

Toxic Unbelievable pll-4

Unbelievable pll-4 Ruthless pll-10

Ruthless pll-10 Seven Minutes in Heaven tlg-6

Seven Minutes in Heaven tlg-6 Pretty Little Liars pll-1

Pretty Little Liars pll-1 Pretty Little Liars #11: Stunning

Pretty Little Liars #11: Stunning 4.5 The First Lie (the lying game)

4.5 The First Lie (the lying game) The Amateurs, Book 3

The Amateurs, Book 3 Wanted pll-8

Wanted pll-8 Lying Game 00: The First Lie

Lying Game 00: The First Lie The Amateurs: Last Seen

The Amateurs: Last Seen The Lying Game #6: Seven Minutes in Heaven

The Lying Game #6: Seven Minutes in Heaven Pretty Little Liars #14

Pretty Little Liars #14 All the Things We Didn't Say

All the Things We Didn't Say Stunning pll-11

Stunning pll-11 Heartless pll-7

Heartless pll-7 The Lying Game tlg-1

The Lying Game tlg-1 The Elizas_A Novel

The Elizas_A Novel Perfect pll-3

Perfect pll-3 Burned pll-12

Burned pll-12 Twisted pll-9

Twisted pll-9 True Lies: A Lying Game Novella

True Lies: A Lying Game Novella Pretty Little Liars #9: Twisted

Pretty Little Liars #9: Twisted Two Truths and a Lie tlg-3

Two Truths and a Lie tlg-3 Crushed pll-13

Crushed pll-13 Pretty Little Liars #15: Toxic

Pretty Little Liars #15: Toxic Pretty Little Liars #12: Burned

Pretty Little Liars #12: Burned Killer pll-6

Killer pll-6 Pretty Little Liars 14: Deadly

Pretty Little Liars 14: Deadly